There is a gap between rhetoric and evidence regarding the business case for sustainability, writes Richard Hardyment. Tackling it should be a priority.

Many companies talk about a business case for sustainability. Investing in responsible business practices can cut costs, reduce risks, build the brand and inspire new innovations. The theory sounds enchantingly simple. But truth be told, hardly any companies publish any evidence to back up these claims. How can we get more businesses to evidence the business case? Companies first need to ask why they are doing sustainability. Then you can apply four simple words to measure everything: costs; revenues; today; and tomorrow.

The moral case vs. the business case

Responsible business has always had a tension at its heart. On the one hand, there are those who argue that without a clear business case, sustainable approaches will languish as a side show. Companies need to make a profit for their shareholders, so investments can only be justified if they create long-term financial returns. On the other hand, there are the moralists. This group – which includes many business executives – argues that companies must embrace responsible business for ethical reasons. Let’s be clear that for publicly listed companies, this means using other people’s money (investors) for moral ends. The moralists’ reasoning is that we need to preserve our planet for future generations (who will bear the costs) and behave in ways that society expects because it’s the “right thing to do”. They make the vital point that sometimes doing the right thing costs money. Paying your employees a decent wage or turning your back on corrupt business practices might mean higher expenditure or forgone sales.

In the long-run, however, behaving in a responsible way ought to make business sense too. Who wants to buy products from an unethical company? The license to operate may be undermined as regulators bear down on you (as the banks have seen and car manufacturers could now experience). So are the business case and the moral case actually the same thing? Not quite. Moralists argue that companies should do the right thing even if no-one ever found out. For them, working out a fully costed business plan simply doesn’t make sense.

Motives guide decisions

The reason why this difference matters is because motives affect decision-making. If companies always seek to act in the best long-term interests of their shareholders, a return on investment needs to be made. I know of one bank that refuses to invest a single dollar in sustainability initiatives unless a fully costed business case is produced. That means calculating incredibly tricky sums like by how much brand reputation might be enhanced through a community project or a more ethical supply chain.

Conversely, if companies are urged to do “the right thing” irrespective of the business case, the question arises: where should you stop? The firm could pay all its employees (and suppliers) ever-rising wages, invest in world-leading environmental technologies, and pour millions into a pipeline of socially responsible innovations – then go bust because the company isn’t financially viable. Business failure means unemployment, and that benefits no-one.

Clearly a balance needs to be sought. There are overlaps between the two motives. The time horizon is critical to working out whether we are talking about just a moral case, or a business one too. Any organisation should begin with the programmes where a clear a business and a moral case can both be made. That requires some calculations of the potential advantages. That brings us back to those elusive benefits. How should we go about putting some numbers on them?

Where are all the examples?

Few organisations publish any evidence to back up their claims around commercial advantages (more are working on them behind closed doors). Corporate Citizenship recently researched the best examples of published data from companies from around the world. These firms are not just claiming business benefits – they are able to cite figures of the impact on the top and bottom line.

GE has invested $19.3 billion since 2004 and generated $200 billion in new revenues from its ecomagination products that solve energy challenges. Nestlé has annual sales of nearly 11.6 million Swiss francs from its affordable and nutritious “Popularly Positioned Products”. Ikea has revenues of €641 million from products that enable a “more sustainable life at home”. On the savings side, there are further examples, including Unilever, which has avoided costs of around €600 million in the supply chain from eco-efficiencies since 2008. But most companies are woefully silent on the matter. They have no data to show.

Profit and loss accounts

A few organisations have produced a profit and loss (P&L) account. PUMA is the most well-known example, but Shell in Germany published a triple bottom line account in 1975. Let’s be clear though: an environmental or social P&L is not a business case. Calculating the external costs and benefits allows for a comparison between business performance and the impacts on society. However, lining the numbers up side by side does not, in itself, provide evidence for doing anything differently. According to research by Trucost, the real environmental costs of the farming, cement, coal, iron, plastics and snack food industries are greater than their revenues! The total costs of greenhouse gases, water and air pollution (including health costs) from cattle ranching enterprises exceed the sector’s revenues sevenfold. So anyone performing these calculations would be forced into a shocking conclusion: the company destroys more value than it creates.

Of course, cattle ranching and coal power are still in business because the current, internal costs of environmental damage don’t affect their financial performance. The real value of this numerical wizardry comes from the future costs and benefits. Forecasting a global price of carbon into these models, for example, allows for an estimate of the potential impact on operating expenditures in years to come. Producing a water-saving device for a small consumer market today may grow into a large source of revenues in an increasingly water-scarce world.

Four words that make a business case

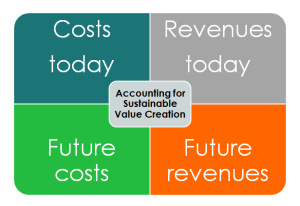

Calculating a business case for sustainability comes down to four words: costs; revenues; today; and tomorrow. All business benefits can be categorised into this 2 x 2 model. Firstly, there are costs saved today (in the most recent year), such as reduced bills through energy reductions or savings from lower staff turnover as a result of being a more attractive employer. These can be easier to make estimates for (though it gets complex when distinguishing new efficiencies from those that would have been made anyway). But the fact that so few companies have these attempted these calculations shows how challenging the whole exercise can be.

Next, there are the revenues today. This would include any sales from a product line that the company has deemed sustainable. It could be an environmental product or a socially-beneficial innovation. An uptick in sales from a cause-related campaign could also go into this category. New sales as a result of a business model innovation are also part of the picture, such as top line growth from accessing hard-to-reach consumers through small-scale distributors in the developing world.

Next, there are the future impacts. The expected taxes from a future carbon price will be tomorrow’s costs. You can calculate a range of the possible expenditures that might be avoided. The same might be done for water, air pollution, biodiversity and waste. Any potentially avoided costs for the company from new regulations, or better relations with stakeholders, would also fit into tomorrow’s costs. How much might be saved from having a happier, healthier workforce with lower turnover, less sickness, less litigation, fewer strikes and higher productivity in years to come?

Finally, there are the revenues tomorrow. This includes the potential fruits of current investment in the R&D pipeline. Many businesses readily forecast revenue ranges for new products. The trickiest area is putting numbers on more fuzzy concepts like brand reputation and stronger relationships with stakeholders. It’s all very well hoping that sustainability is good for the brand – but what might be the impact on the top line? This is incredibly challenging. Estimates can be made for the impact on future sales from an improved brand perception, teasing out how higher ethical standards or creative collateral for brand campaigns compares to a business as usual scenario. In theory, you might also be able to work out future sales ‘saved’ by a better reputation – if critics and campaigners don’t come after a company because it’s put in place more responsible practices.

Guesswork is hard work

As you’ve probably realised by now, putting estimates on all these dimensions is hard work. Most require some educated guesswork, drawing on previous experience and peer learning. The complexity of it all is one reason why so few companies have published the evidence to back up their claims. For many, fears around commercial confidentiality, particularly over revealing the size of a market for new products, adds to the caution.

A second complication is exactly how to define ‘sustainable products’ for those revenues. Some take a very broad definition and include making adjustments to the product profile. L’Oreal has a target for 100% of its products to have some environmental or social benefit. This will be reached by making changes to the whole portfolio footprint from sourcing, production and packaging. This all-encompassing approach is very different from segmenting the portfolio into “sustainable” and “non-sustainable” products according to strict criteria. There is no right answer here. Even GE has been criticised for including gas, and fracking solutions, as part of its ecomagination revenues. If you opt for strict in/out criteria, critics may ask: why are you still producing any unsustainable products?

By far the biggest challenge is that companies cannot measure everything. Intangibles like reputational advantage are a case in point. The marketing industry is starting to wake up to the need to measure benefits beyond just a Net Promoter Score, such as the societal impacts of marketing and sponsorship. Even the best brains in metrics struggle to put figures on the intangible benefits that arise from corporate community investment. Great strides are being made by organisations like LBG, but there is still a long way to go. It may be many decades before we have a fully costed estimate of all the business benefits from responsible business practices.

Does this gap between rhetoric and evidence really matter? It does. Without evidence, there will always be some within businesses who just won’t get it. Calculating the business benefits is essential to accelerating the trend towards a closer integration between responsible business and core commercial priorities. Professionals working in companies who want bigger budgets and faster changes need to get to grips with these calculations just as the supply chain, marketing, HR and other functions do for their priorities. In an increasingly competitive business environment, demands for a robust commercial case are only going to increase.

Companies need to explore the business case with more rigour and realism. At the same time, we need to acknowledge that we simply cannot measure everything. But a lack of data should not put the brakes on progress. Where it’s just not possible to estimate a return, the moral argument can still be valid. Calculations can be made. Forecasts can be attempted. But, occasionally, it’s just worth going for it because it feels like the right thing to do.

Richard Hardyment is an Associate Director and Head of Research at Corporate Citizenship.

COMMENTS